A Deeper Dive: Investing in Emerging Market Debt

by: Smith and Howard Wealth Management

In a nutshell: At Smith and Howard Wealth Management, our clients are our top priority. They trust us to make wise investment decisions for them, knowing that we always act in their best interests. In part, that means continually educating ourselves about investment opportunities, which can change over time. What may have been risky in the past can sometimes gradually evolve into a more solid investment. We put significant thought and research into the decisions we make on behalf of our valued clients, especially when it comes to diversifying investments. The following installment of A Deeper Dive talks about one of those diversification options.

The idea of global diversification is typically something investors associate more with stocks than with bonds or fixed income. In fact, it is now a common and accepted best practice to diversify an investor’s equity holdings outside of their home country (obviously, in our case the U.S.). The same type or level of diversification is far less commonplace in fixed income. Sound reasons exist for why that has historically been the case, but as we’ve stressed over the last few years, we believe that in order to have continued investing success we must be agnostic to where the opportunities are. One such area that we find compelling is emerging market debt.

What is emerging market debt?

Emerging market debt is a term used to describe debt or bonds issued by less developed or emerging countries, as well as by corporations based within those countries. Emerging market debt, both government and corporate issuances, may be denominated in either U.S. dollars (typically referred to as “hard” currency debt) or the local currency of the issuer. U.S. investors have typically opted to own hard currency debt since it removes much of the currency risk and volatility.

The evolution of emerging market debt

U.S. investors are naturally and understandably wary when it comes to investing in emerging market debt. In addition to the fear that some investors have of anything considered “emerging”, the asset class has an inauspicious past that creates an additional hurdle. While that history shouldn’t be ignored, much has changed in emerging markets over the 20 years since the last extensive, credit-related emerging market crisis.

The beginnings of emerging market debt as an investing option can be traced back to the 1960s and 1970s when Latin American countries, namely Brazil, Argentina and Mexico, on the back of soaring economies and commodity prices, borrowed large sums of money for further economic development. Commercial banks, flush with cash from oil-rich countries, began to replace the World Bank as the primary lender to these developing countries. Between 1975 and 1982, Latin American debt to commercial banks increased at a greater than 20% annual rate and resulted in a quadrupling of external government debts. While the increase in total debt was startling, the cost of servicing the debt increased at an even faster clip due to surging global interest rates.

Like most leverage or debt-related crises, a tipping point was eventually reached. In this case it came in 1981, when world trade began to contract and the commodity prices that Latin American countries had come to rely so heavily upon fell. In August of 1982, Mexico became the first of these countries to announce that they would default on their debt. Not surprisingly, this led most commercial banks to quickly reduce or halt any new lending to Latin America. As much of Latin America’s loans were short-term, a crisis ensued when other countries, unable to refinance or repay their loans, were also forced to default. Defaults led to debt restructurings, but these attempts proved unsuccessful and led to what Latin America calls its “lost decade” of high unemployment and stagnant economic growth.

By the late 1980s, it became clear to the U.S. government that a more drastic, comprehensive solution was needed to break the cycle of restructurings and defaults. In 1989, then-U.S. Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady announced a debt-relief program that would convert defaulted commercial bank loans into a variety of new bonds that became known as Brady Bonds. In return for their reduction in debt, countries agreed to undertake meaningful structural reforms intended to increase the stability of their economies. This program successfully drove an increase in institutional investor interest and ushered in a new era for emerging market debt.

Despite the success of the Brady Plan, the period of the 1990s continued to see emerging market countries and their debt markets encounter growing pains. The Mexican Tequila Crisis (1994-1995), the East Asian financial crisis (1997) and the Russian financial crisis (1998) all tested the resolve of investors. In fact, six of the eight worst months on record for the Bloomberg Barclays Emerging Market USD Aggregate bond index (incepted January of 1993) occurred in the 1990s. The other two difficult months occurred during the 2008 global financial crisis and were not specific to emerging markets. For many investors, the experiences and stories of the 80s and 90s have continued to influence investors’ appetites for the asset class. Much has changed since the late 90s and the last broad emerging market crisis, but investor perception isn’t necessarily one of them.

What has changed?

It would be naïve to say or think that emerging markets haven’t experienced complications since the late 90s or that they won’t experience them in the future. After all, emerging countries are considered “emerging” for a reason – less political stability, less stringent accounting standards, domestic infrastructure problems, etc. As one emerging market debt manager recently phrased it, “It’s emerging markets: of the 70+ countries in the index, a handful of them will do something stupid every year”. So why would we be interested in investing in an area that is prone to issues? Three reasons: improved country-level discipline; a broader, more diverse investment set; and attractive relative yields that compensate investors for the additional risks.

1. Improved country-level discipline

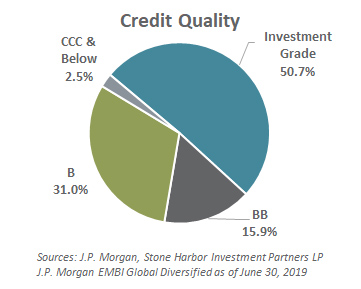

Since the late 90s and the last broad emerging market credit crisis, many emerging market countries have instituted major economic and financial reforms. Not wanting to revisit the sins of their past, these countries have shored up their financial stability by increasing foreign currency reserves, letting their currencies float freely, and reducing frivolous public spending, all of which has led to improved and more stable debt/GDP ratios. Contrary to what one may expect, emerging market countries now compare quite favorably relative to the developed world when it comes to debt/GDP ratios. Also surprising may be the fact that emerging market hard currency sovereign (i.e. government) debt is predominantly investment grade (see Credit Quality chart).

Despite broad improvements, it is important not to overgeneralize. Emerging market countries have economies and markets at various stages of development, as well as different currencies, political landscapes and policy stances. That diversity leads us to our second point – a broader, less concentrated, less correlated investment opportunity set.

2.Broader, more diverse investment opportunity set

If we revisit our discussion on the evolution of emerging markets, you may note that there appeared to be a consistent theme to what transpired. The growth in lending was across just a handful of Latin American countries that all tended to be heavily dependent upon a continuance of an oil/commodity price boom. When the first of those countries, Mexico, announced they would be forced to default, it created a contagion effect throughout the rest of the Latin American countries that had taken on considerable debt.

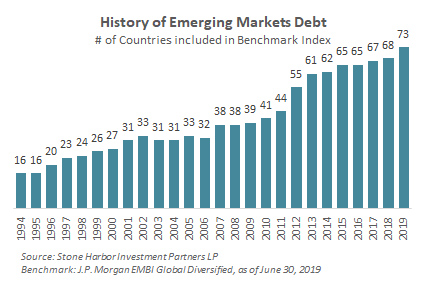

The current emerging market debt universe bears little resemblance to the one that was created as a result of the Latin American lost decade or the Brady Plan. Not only were there just a handful of countries with debt outstanding at that time, but there was also an equally small universe of interested investors. Neither of those characteristics is true today. As the graph below illustrates, the number of countries that have issued US$ (hard currency) debt has more than quadrupled since the early 1990s. That number does not include additional emerging market countries that have issued debt in local currency or have corporate debt outstanding.

The increased diversification of issuers has helped in reducing the contagion effect. Emerging market countries have and will continue to encounter difficulties, but incidents have become more isolated or country specific. To be fair, that doesn’t mean emerging market investors don’t still worry about contagion risks. In fact, when any country, emerging or developed, encounters debt issues or stress, the first instinct of investors is to try and figure out which other countries might be in a similar position. Due to its history, that mindset is probably a bit more prevalent within emerging markets, but as that market has grown and matured, investors are increasingly aware that every country and situation is unique. It is also worth noting that since the early 2000s, every major credit crisis with broad market implications has originated not in emerging countries but in developed countries (Lehman Bankruptcy, European Debt Crisis, Taper Tantrum, Oil Price Decline).

3. Attractive relative yields in low yield environment

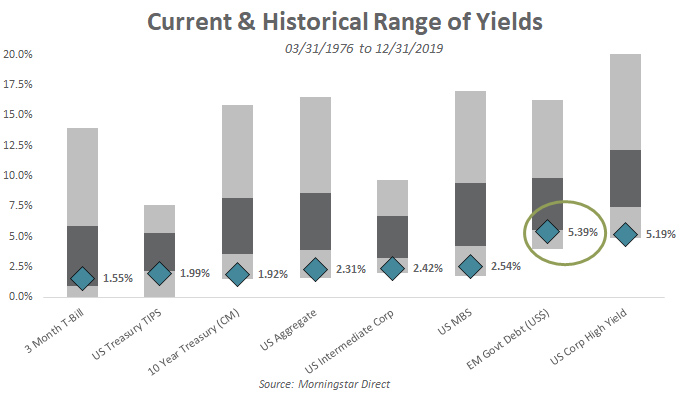

To long-term, value-oriented investors, the improvements in credit quality and the increasingly broad opportunity set within emerging market debt means little unless it also comes at an attractive valuation. It may be difficult to argue that emerging market debt is excessively cheap, but it is attractive relative to almost every other area of global fixed income. Despite an average credit rating of investment grade, emerging market hard currency government debt tends to have yields similar to that of U.S. non-investment grade or “junk” bonds. In the accompanying graph titled Current & Historical Range of Yields, we show several different major segments of the fixed income universe. Each grey bar represents the historical range of yields over the time shown and the blue diamond is the yield at the end of December 2019. As the chart illustrates, emerging market government debt denominated in U.S. dollars (EM Govt Debt (US$)) has a yield higher than that of U.S. Corporate High Yield, despite a higher average credit rating.

It is no coincidence that we intend to fund our position in emerging market debt by reducing our exposure to U.S. Corp High Yield or what we may refer to as Opportunistic fixed income. We believe such a move will benefit portfolios by improving the overall credit quality and increasing diversification without sacrificing meaningful overall yield or return expectations. We believe the diversification benefits and overall value fairly compensate us for the risks of the asset class.

Contact Brad Swinsburg, 404-874-6244 to learn more about Emerging Market Debt as an investment opportunity.

Explore more information on the fourth quarter of 2019 by visiting these links:

Market Recap + Outlook: Fourth Quarter 2019

On the Horizon: Fourth Quarter 2019

Unless stated otherwise, any estimates or projections (including performance and risk) given in this presentation are intended to be forward-looking statements. Such estimates are subject to actual known and unknown risks, uncertainties, and other factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from those projected. The securities described within this presentation do not represent all of the securities purchased, sold or recommended for client accounts. The reader should not assume that an investment in such securities was or will be profitable. Past performance does not indicate future results.

Subscribe to our newsletter to get inside access to timely news, trends and insights from Smith and Howard Wealth Management.